What are user interviews?

Well, for me, that's just a fancy way of saying I'm hopping on calls with users to watch them use the software. I walk them through the optimal usage of Numenon for their specific scenario, intervening as little as possible, to see where they naturally head.

While doing that, I note things like whether or not they find a button easily, what catches their eye, what they seem to grasp easily or struggle with, and so on. At the end, they give me open ended feedback and then we part ways amicably. Unless, of course, they say something bad, in which case I banish them to the depths of Khazad-dûm. Just kidding. Mostly.

Then comes the sorting of the feedback to actionable tasks, and whether these will go to a specific release or stay in the icebox until way later. It all depends on how often a specific issue comes up, weighed against our own evaluation (unsurprisingly, we're our most active users at this point).

Well, user interviews are a curious beast.

And in all their curiosity or greatness, they resemble a "rubber duck" situation.

What's a "rubber duck"?

Well, apart from the cute little toy one uses for a whimsical soak in the tub, "rubber duck" is also a development term.

As programmers, we spend a large part of our lives debugging (often more than coding), and we frequently get stuck. Sometimes, when you describe an execution flow from start to finish to someone else, your brain hits that 'a-ha' moment and you suddenly spot where the bug lies.

But programming is often a solitary profession, and you might have no one to talk to. Enter the rubber duck. You plonk it right next to you and tell it all your coding problems. I guess you can do it with your relationship problems too, but it might start charging you.

Ok, back to user interviews.

They can be extremely useful or dangerously misleading.

And it’s mostly about detecting patterns.

If a certain number of users have a difficulty with x or y, then you know you need to work on x or y. Or, if a specific workflow sparks joy, lean into it. Keep it, protect it, maybe give it a bit more spotlight in the UI.

But you must be careful not to put too much focus on one user's opinion. She may be convincing, present great arguments, but she is still just one data point. You must not allow yourself to get carried away. Note the feedback, but don't act on it yet. Unless...

Unless she is the archetype for your target audience. If she perfectly represents the specific group you are building for, then it doesn't matter that she's just one, her single voice carries the weight of a whole audience.

A lot of variables to juggle.

But, in any case, regardless of whether the feedback itself is directly applicable, the process is always useful.

And here is where the rubber duck comes in.

The rubber duck lens

By walking through your app with a new user, you see it through their lens, a new one.

That's the most valuable part of it all, I think. Having the opportunity to view your app with fresh eyes. And that has both positive and negative aspects, in the sense that you'll probably see A LOT of things that need improvement, especially during early stages.

But, you also see it as a creature of its own. A wonderful creature that you fall in love with all over again.

My Journey with the Genre

My first contact with the genre was a game called A-Train in the mid-90s. I remember being fascinated by watching my city evolve. I felt like a gardener tending my plants and flowers. They would flourish or die depending on my actions. What an amazing discovery for a kid! I didn't really understand what I was doing, but I knew that things were happening. The city was alive. Later, I enjoyed all the popular SimCity titles for thousands of hours, along with Cities XL and later the Cities: Skylines series. Recently, I've also tried Citystate 2 because of the hype around the new trailer for Citystate Metropolis.

As a programmer, I understand why it is such a difficult task to create a city-building game that will make everyone happy and keep your PC from exploding. But as a player, when they announce a new game, I really feel like that 10-year-old kid waiting to finish school to go and build his city.

Citystate 2 is like SimCity 4 with Politics

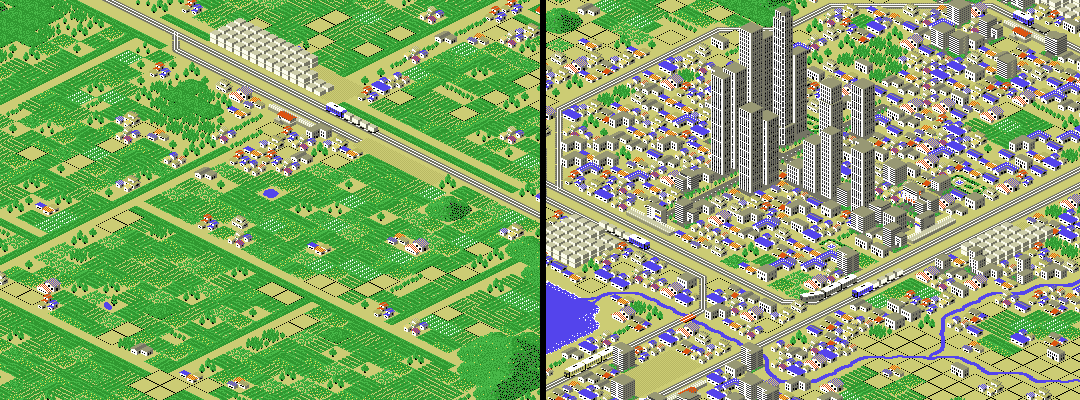

Citystate 2 is SimCity 4 with politics and a more complex economy. When I started playing Citystate 2, I began to experience the same feelings and reflexes as with SimCity 4. Mind you, I haven't played SimCity 4 for over 15 years, so I had no recent memories. After playing Cities: Skylines for so long, I had forgotten how different the experience was.

It is remarkable that one person managed to create Citystate 2. It's not perfect, but it could easily be considered SimCity 4.5. Maybe I'm wrong, but it's like the creator had a vision to take SC4 and add a deeper social and political layer. And he did that. He didn't try to innovate on the city-building part. He kept all the SC4 concepts almost identical.

In both SC4 and Citystate 2, there was a constant balancing act of bringing more people into the city to increase income from taxes while ensuring the infrastructure could handle it. This was the main loop for all my playthroughs: zone stuff, make money, expand infrastructure, lose money, zone stuff, make money, you get it. Playing with policies and making experiments was also fun. I enjoyed taking actions and anticipating how my citizens would react.

The downside of that experience was that it didn't allow me to be creative with my city. The pleasure of designing my city to look and feel realistic wasn't there. I just acted in order to influence the simulation. In the Cities Skylines games, I take great satisfaction from planning an area and manually placing intersections. I don't care that much about money and taxes. What I care about is whether my city makes sense. Does it look and feel realistic? Watching all the trains and vehicles carry on their tasks and blend together is really amazing. On the other hand, I miss the strategic aspect of how to make the city survive. I miss the feeling that the environment (both economic and physical) reacts to my actions. Is it possible to have both?

Cultivate the Environment

A skyscraper in SimCity 4 was the result of the sum of many parameters. Something difficult to achieve. An accomplishment. You had to create the circumstances in which a skyscraper would finally emerge as a testament to your city's evolution and economic success. In Skylines, it just happens. Too easy. Too anticlimactic.

I am not saying, just make skyscrapers difficult to make city-building more interesting. My point is that the idea of cultivating your environment to get results is a very satisfying game loop. Not only for good outcomes but for bad ones too. And cultivating the environment can extend to economic strategy, social policies, zoning decisions, transportation and the list goes on.

I should mention here Urbek City Builder, which is built around that idea. The game's core mechanic revolves around environmental cultivation. Buildings automatically upgrade based on their proximity to specific resources and neighboring structures.

Talking about bad outcomes brings me to another matter. It puts me off how clean everything is in Skylines. It looks plastic and fake. Where is the wear, the dirt? Where is life? I need the game to reflect time. Buildings get old and classic, roads crack and no one cares, neighborhoods can become slums, others will get gentrified.

Cities: Skylines' pitch focused on cities that tell stories. But how can you tell stories with a plastic clean environment? The models are lifeless. There is the option to manually add decals and such, but this is not the same as having the simulation react to the environment. I would prefer a game called Cities: Timelines to Cities: Skylines.

SimCity 5 Was a Magical Disaster

A revolutionary disappointment. A dream turned into a nightmare. The artistic style, although too playful for my taste, was implemented to perfection. The sounds and animations were stunning. The soundtrack was majestic. The anticipation made me feel like a child again waiting for Christmas.

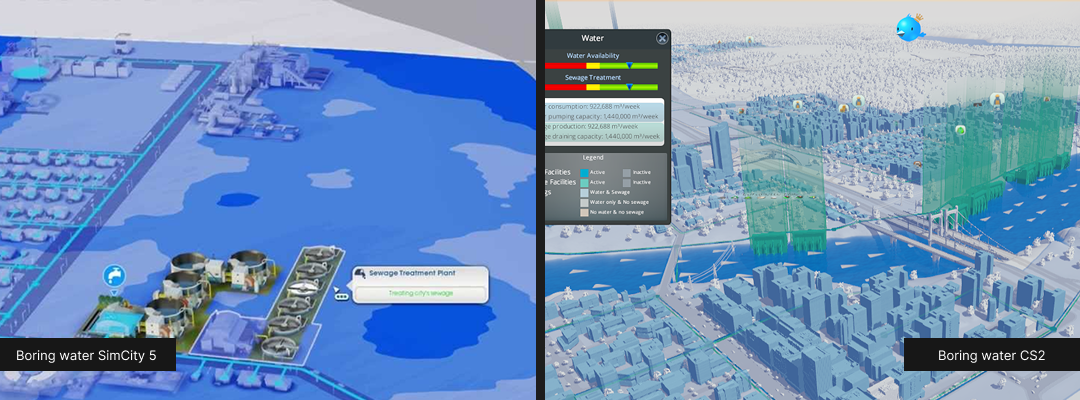

I will not get into the details of why it was a disaster. We all know. The technical novelty was the agent-based system. A new blueprint for city-building games emerged where agents replaced the macroeconomic simulation. Cities: Skylines found the perfect timing to sell water to all of us, hyped and left dry. But they didn't try to create a better SimCity 4. Instead, they went to make SimCity 5 with more space and no multiplayer. We never got the "real" successor to SC4.

The Two Models of City Building

In SimCity 5 and Skylines 1 and 2, the outcome is now the result of agent behavior. The agents drive the economy based on some rules. They do their pathfinding, they buy stuff, they have an internal state. The sum of their behavior creates the final outcome. In contrast, in the macro-simulation model of SimCity 4, the algorithm reacts to user actions and then renders the reality. I know that this is a very simplistic explanation but the point is, these two models are entirely different. The agents are "what you see is what you get" in a way. A one-to-one representation of what is going on. The rules are hidden and they manifest themselves in ways you wouldn't always understand. Even the developers can't reliably predict. Agents are too dynamic in nature. Unlike the agent models where the process is visible in front of you, in the macro model the process is hidden and you just see the outcome.

I know that it's not accurate, but for the purpose of this text, I will refer to these two models as the "agent model" and the "macro model".

The macro model can be magical as you see a delayed reaction to your decisions, but it can also become quite boring when the rendered reality is not "real". The agent model opens up more interesting behavior. It just looks more like real life. You can "touch" every single one of your citizens. Everything is in front of you. And this is beautiful. But a lot of problems come with that, because the agents' interactions can be unpredictable and chaotic. Controlling and balancing the game as a developer could be tedious or nearly impossible. Another problem is that we players want to make cities with millions of citizens. And none of the three attempts seem to be able to deliver that. Is it impossible?

The Next Model

I think most players agree that the macro model is a step back. On the other hand, the agent model seems to have a computation limit and some serious balancing issues. So what is coming next? Is it a combination, or does something entirely new wait in the corner to be discovered?

I will attempt to break down some aspects of the game and demonstrate how I would structure a solution. Given that I don't have access to the code, my critique may be inaccurate or wrong, but I will give it a shot anyway.

In all the agent-based releases I noticed that they fall for the hammer case: "When you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail". Agents are everywhere. I suspect that this made sense for economical reasons. Once you make water work like that, why not make electricity and trash, education and the police and everything work in a similar fashion with some adjustments?

Water and electricity are extremely boring topics. They are just something that you have to do. Nobody admires the power line transferring electricity to the houses. Every couple of hours of gameplay you just have to manage the system to have adequate production. Does the agent system enrich the experience? No. Would a simulation approach free up some resources? I don't know. But if it does, then it's a no-brainer. Same with water and waste management.

Regarding deathcare: This is one of the most stupid things in the Cities Skylines games. The idea of managing the dead can be realistic. The fact that you have hearses flooding the streets is not and it is just not good game design. It is crystal clear that deathcare should not be another nail for the hammer. The question is which part of the deathcare makes sense to rely on the agent system and which part should be handled in another way to achieve a realistic representation.

This is a good scenario that someone should brainstorm on. One proposal is to create a "translator", a connection between the agent world, the macro model, and what the user will actually see. It doesn't matter how, but an agent representing a person will die at some point, either by an internal state rule or forced by the macro model. It doesn't matter. Our goal is to have a realistic death ratio on paper and a realistic representation in the actual city. Not having 15 hearses stuck at a traffic light.

In order for the game to be fun and engaging, the players have already accepted that time and space are not realistic. This is a significant abstraction. An agent looks, moves, and behaves like we are in the real world. But it will take an in-game time of 1 day to go from A to B, where in real life this would be a two-hour trip. For some reason we retain our immersion. I will assume that players want to see agents behave exactly as they do in the real world and at the same time are fine with letting time and space run in an imaginary representation. Players also need real numbers on building capacity. Real numbers on city management. Cars, services, and everything live and breathe as in a real city. Do you see the gap? We have parallel "simulations" running. Or we should have. One should take care of the macro numbers. One should take care of the agent representation. One should be the balancer between the two.

Back to the deathcare. A possibly better approach would be to let the macro model generate realistic numbers for death cases. Is it an epidemic, is it a normal situation, is it the boomer generation getting very old? Make the numbers make sense. Now use the "translator" to express that in realistic representation in the agent model.

The Absence of Construction Industry

A player decides to zone 100 houses at once and the game says "Fine! Give me 5 minutes and you will have 100 houses ready with 500 population". This is an unrealistic spike in the ecosystem. How could the city sustain the parallel building of so many houses in terms of material, workers, infrastructure, etc.? It's not realistic and it is the source of many problems down the line. "There is no such thing as a free lunch". This complete absence of the construction industry is a lost opportunity.

Having a construction industry would solve part of this problem and contribute to more interesting gameplay. The construction industry would trigger new construction projects, gentrification projects, maintenance, and repair of existing buildings. It would require offices, warehouses, and related industry and be part of the market for materials and resources. It doesn't have to be granular and detailed. It can be incorporated into the existing economy dynamics.

Workers & Resources: Soviet Republic is game that uses this idea. It treats construction as a simulated, multi-step industrial process that requires resources, vehicles, and workers, effectively making construction a key part of the in-game economy and agent simulation.

In this scenario, a player would get the best of both worlds. Construction becomes immersive and meaningful. It's not an unlimited resource. And the player can influence via taxes or incentives the construction capabilities of the city, which in turn will define how quickly we can build and maintain existing infrastructure and buildings.

Elevation, Perfection and Imperfections

When Skylines 2 was released, I was deeply disappointed with zoning. To me, it's unimaginable that a new city-builder doesn't support curved zoning and variability in elevation. Buildings zoned out of a strict grid are ugly and jellified with unnecessary gaps. Zero innovation from the previous game. Sure, you can use mods, but still, I don't want to place all the buildings by hand and hide imperfections with bushes and trees.

I am not saying that it is not a tricky problem, but I am sure that solutions can be found and this problem converted into a feature. Convert this miserable situation to interesting gameplay. Allow the player to decide and manage construction on difficult terrain. I am not knowledgeable on the subject, but I guess you can have some options like: build a flat platform, integrate the building on the slope, flatten the land, or build on incremental levels. Give options for the road behavior. Introduce steps in the pavements, different walls, and have a minimum rectangular concrete level to avoid the jelly effect. Imperfections in city design can become a feature and give character to communities.

Plopping and Forever Stuff

There are 2 things that I really hate and don't understand: plopping buildings and "forever stuff".

Plopping the same building again and again is boring. Why plop the police station and not just "design" a police station that will grow like other buildings? Let me choose architectural style and give me 10 components. Let me lego my way to a unique combination. This can be applied to buildings, parkings, complexes, services, and literally anywhere. Let me expand horizontally or go vertically. Let me make it small or huge. Once I've designed it, don't plop it, let the construction industry take action.

Regarding the forever stuff: I build a road and it will be forever clean, painted, and pristine. Same with parks, same with buildings, same with everything. Let everything evolve, age, decay, get dirty, and potentially get renewed and be fresh again.

Dreaming of a Million People

For some reason, a million people is the bar a city builder has to pass. But why a million? Why not 2, 3, or 15 million? If your goal is realism, a million limit is still not good enough. Most famous big cities have way more than 1 million people. The agent model seems to be close enough to achieve this. But what about 10 million people? How could the agent model achieve this?

Before I continue, it is a good time to recap some things mentioned in this text:

- The agent model alone is hard to control and provide a realistic outcome

- The macro model provides better control over the economy dynamics

- The agent model mimics reality in a very engaging way

- The macro model "fakes" the rendered reality and becomes boring soon

- The agent model needs very powerful computers to simulate large numbers of agents

Back to the question: How can we simulate millions of agents without frying our CPU? One solution to that kind of problem is clustering or agent aggregation. I will not get into details, but the idea is to group the agents in ways that make sense and reduce the computation needs. If you combine agent aggregation with our macro model, then maybe a new design will possibly emerge.

Time

I don't think that I have to debate that keeping time and space realistic would make the game unplayable. Players accept more easily abstracting time than space. The problem is: how do you model realistic traffic patterns and human behavior when time and space are not realistic at all? This is a hard problem. Some things you can abstract, some other things you can't. What is the goal? To maintain the immersion! Keep the macro model's numbers real and render something that makes sense.

In the current agent model, in my opinion the problem is that the agents are responsible for far too many things. They have to actually do their tasks, be visible in real-time as they do their tasks, and as a whole, achieve a balanced economy and a realistic representation for the player.

I'd argue that this could actually be possible if the goal was to achieve a realistic 1-to-1 simulation. But we decided that time should be different, and space should be different, and so many other variables are absent because it's a game!

Something has to balance out what was taken out of the equation.

A New Hybrid Model

I often wonder how I would design my dream city-building game. Maybe I am naive, maybe I am just wrong, but I will give it a try regardless.

A macro model will be responsible for managing the economy dynamics and setting the tendencies. A clustered agent model will be responsible for representing what is going on in the macro model. Between them, the translator converts numbers to agent behavior that makes sense in our altered time-space. The flow of the information will be one way and look like this:

Action → Macro Model → Translator → Agent Model

The macro model will be responsible for taking any action and transitioning the simulation to the next state. The translator is responsible for receiving the next state and manifesting it in the agent world.

An example: The macro model identifies that an area has high pollution. According to our formulas, a percent of the population should get sick. Let's say that 10,000 people live in that area and 10% will get sick each game year. That will result in 1,000 people sick. We know that 1,000 ambulances flooding the city is not realistic to see and certainly not possible to get processed in the user's system. And if you remembered, we abstracted time and space, so why not do the same with our sick people? The translator decides that 20% will be a realistic representation for the user and it will decide to spawn 200 agents in the course of a game year. The final outcome will be: realistic numbers when investigating your city stats, real agents running around the city making it look alive, and more optimal for the CPU.

The most important aspect of this approach is that it is reproducible and testable. You are not at the mercy of chaotic agent interactions. The agents are not responsible for running the economy. They just represent it in a way that immerses the user and is analogous to the economic dynamics. As a developer, having 3 individual systems, testing becomes more practical. The macro model takes the input and moves the game to the next state. The translator takes a game state and "demands" a representation from the agents. The agents receive the desirable outcome and regulate their behavior over time.

Potential New Problems with the Hybrid Model and Some Suggestions

Very briefly because this text is becoming too long. In order for the translator to be efficient and not become the new bottleneck, I would suggest 3 strategies:

- Have "templates" or cached commands for common scenarios or uninteresting events

- Batching computations: The translator should not be sensitive to every little game state transition. It should wait to compute only significant amounts of data. That threshold will differ for each subsystem

- A similar concept to eventual consistency between the macro model and the agent model will also help reduce unnecessary computations

If you are still reading, congratulations and thank you for making it this far. I wrote this text not because I believe that I am more clever than existing developers. I am not. I did it because I love the genre and I hope that a team of more capable people than me will potentially get inspired by some of these ideas.

Peace

Some great positions in the comments:

Discussions:

]]>Numenon is an ambitious knowledge base management system in its early stages. Our first closed beta release was back in May. Built with PHP and Laravel on the backend and Svelte on the front. I know, I have some questions to answer. Why did we rewrite? Why Gleam? Why now? Is it good? Was it hard?

What is Gleam

Gleam is a general-purpose, concurrent, functional, high-level programming language that compiles to Erlang or JavaScript. Gleam is a statically-typed language that runs on Erlang's virtual machine BEAM. It has its own type-safe implementation of OTP, Erlang's actor framework.

Why Gleam

My first contact with Gleam was 3 years ago. It was love at first sight. The first thing I thought looking at this new language was "This is exactly the language I would create if I was as smart as Louis, the creator." A small, functional, statically typed language. Only data and functions. For sure, there have been hundreds of small decisions taken during the design of Gleam and its ecosystem. And every time I enjoy the result (pun not intended) of those decisions, I get a warm feeling in my heart.

I felt an obligation to myself to try something new. I had been waiting for years to switch to a language that makes sense to me. I've used PHP, Javascript, Python, Java, Go, Elixir and I've never felt that the language was in line with my style of programming. Go was the only one that I really liked, but still, far away from my ideal language. It would be fair to say that Gleam and Go have some similarities. They are both small, simple, statically typed, not object-oriented, with errors as values. They both enable teams to have a concise style of coding. And I think we are done with the similarities.

I also felt the need to support the Gleam creator and contributors because they made it. They have released an amazing language. And I love it. I want to be an early adopter. I want to express my gratitude with actions by trusting them and showing the world that another Gleam codebase is live.

Why did we rewrite and Why Now

Gleam has been ready for production for over a year and a half. Numenon is in its early stages, so the rewrite was still viable and not totally unreasonable. If Numenon goes well, building on PHP for the next decade was a thought that filled me with terror. Not because PHP is bad. It's just that personally, I had enough of it and I was looking for an alternative.

I am an experienced developer who has survived many rewrites. If you ask me if a rewrite is a good idea, 9 out of 10 times the answer out of my mouth is going to be no. In my case the answer could still be negative, but there are 2 points that minimized the risk. Firstly, the rewrite started as an experiment, never meant to actually replace the existing code. It went so well that we had no reason not to go forward with it. And secondly, the switch to Gleam made our code feel more robust. The gains in productivity from switching were already visible.

3 weeks of Gleam coding

The rewrite took only 3 weeks. Mind that I'd never written a single line of Gleam code before that. The first 2 days were really hard. I was trying to figure out the use keyword in combination with the result module. The videos of Isaac Harris-Holt helped a lot! Another thing that helped me was browsing the "Questions" discussions in Gleam's Discord community.

I dedicated the rest of the first week to making sure that the ecosystem could support all of our needs. And it did. Not all needed libraries were available in Gleam and here is the great fact about Gleam compiling to Erlang. We can use libraries from Erlang or Elixir. That's what we did for sending emails with SMTP for example.

Once I had gained familiarity with the syntax, I created my dev tooling with the help of the Gleam Discord community again. Then I mapped the webserver concepts (routes, controllers, middleware) from PHP to Gleam and the last part was to map the rest of the codebase.

Surprisingly, that was really easy. One reason is that my PHP code was already written in a style that was easy to convert to Gleam. I was using only static functions and everything was as typed as possible. Classes were used mainly for namespacing functions or as data-holding objects. My PHP code would make a PHP developer furious.

Because Gleam is statically typed, all the incoming and outgoing data has to be decoded and encoded. In my case, from Postgres to Records and back. And from JSON requests to Records and back. This was the most time-consuming thing, but at the same time, it was a really valuable aspect of this rewrite. Although in PHP the data was already as typed as possible (generics via static analysis), you can't compete with a statically typed language. Gleam's decode module is a beautifully written tool and with the help of the language server, the task of decoding and encoding all the data types was bearable.

Deployment

Something that started as an experiment was now real. No PHP in the codebase. Just Gleam and Svelte. It took me a day's work to finalize the deployment process.

On the Gleam website there are deployment guides which I ignored, in order to go with something as simple as a 5-line bash script. It runs the tests, bundles the javascript, builds the Erlang shipment, rsyncs it to the server and restarts the service. That's it. I am a happy person.

Production

We are one month in production and have zero issues. I can't offer any insights regarding performance because we don't have that much traffic to draw any useful remarks. The service runs reliably, the "cron jobs" and the queues that now run in the BEAM VM just work. I have to mention though that performance was not a factor for this rewrite.

General Notes and Remarks

Having a clean and organized codebase made the rewriting task so much easier. That was a validation that our architecture was well designed in PHP.

Having Option, Result and use in the language made the flow of the program natural and very easy to read.

We've replaced Laravel queues with the m25 Gleam package. This made infrastructure simpler and local development easier.

The only library that I was missing was a very simple typed query builder. We have a lot of dynamic queries and we had to create our own query builder. It's not great but does the job for now. Maybe we are going to release it one day.

Although Gleam is a small language, the ecosystem has so much to offer for those who want to challenge themselves and dive deeper. On the backend side, OTP is ideal for concurrent, distributed applications. On the front-end, Lustre is a more compromising/pragmatic Elm-like framework with some unique ideas around components and how you "run" them.

Gleam is a beautiful language. Go and give it a try.

]]>To expand or not to expand?

We wanted to describe our services and provide necessary info, but most people don't read texts (so they end up bouncing).

Users often don't want to read more than a sentence. They just want the gist before they engage more with the content, if at all. And that's not just an opinion, that's data.

But still, there are some people who prefer to read more. They get a lot from your style of writing and they want to see if they match with you based on what you have to say and how you say it. They want to connect. They feel they can trust you more. They might even infer you have more expertise when you can expand further.

And I want these people as my clients too, I don't want to lose them just because I decided to "entertain" my audience with minimal content.

For some users, seeing more content might feel overwhelming or like homework. For others, it feels like an invitation to connect more deeply. Our target audience could fall in either pool.

So, we ended up doing both.

We didn't want to do the typical solution of:

A Big Title.

Then one short sentence.

A read more button

Because it's annoying for deep readers to have to click on every Read more button, and either be redirected to another page or have the text broken up with titles and images everywhere, when they would prefer a nice, flowy text.

Instead, we added a simple toggle button that switches between short and long texts. Same sections, same titles, different text length.

Our default is the short version, since that'll probably apply to most users, but the ones who want the whole content can get it with a simple click.

And it was actually fun to make! Trying to express 5 paragraphs in 4 bullets is a cool brain challenge.

I am now seriously considering whether we should be doing this with more of our content. It's not ideal for all types of content, but I think it's a pretty nice approach, especially for sales pages.

As creators, or designers, or communicators of any kind, I think we have several responsibilities.

I know some of us tend to think that we should respect our users' lack of time and attention, and make sure to provide them with the necessary info in the shortest possible way.

And I know that others think that we shouldn't treat people like toddlers, and we shouldn't feed the short-attention-span monster.

I don't know where I stand, personally. And I'm not sure I want this responsibility. It seems a little patronizing, to take on such a role.

At the end of the day, I just want to connect with whoever might be interested in what I have to offer.

PS1: Long content works when it's good. There's a UX argument that it's not always about "making it short". It's "make it meaningful for the right audience".

There's a Reddit thread on /copywriting with a great title (and some great arguments):

"Long pages are not a problem — Bad content is."

PS2: There already are browser plugins that do that for you (of course). I am wondering how long until it becomes a built-in browser feature. Something similar to auto-translate. Right click and "Give me the gist".

"What is improv?" you may ask. It’s perhaps the nerdiest, most captivating, extraordinary, and sometimes downright horrible theatre art form out there. Look it up!

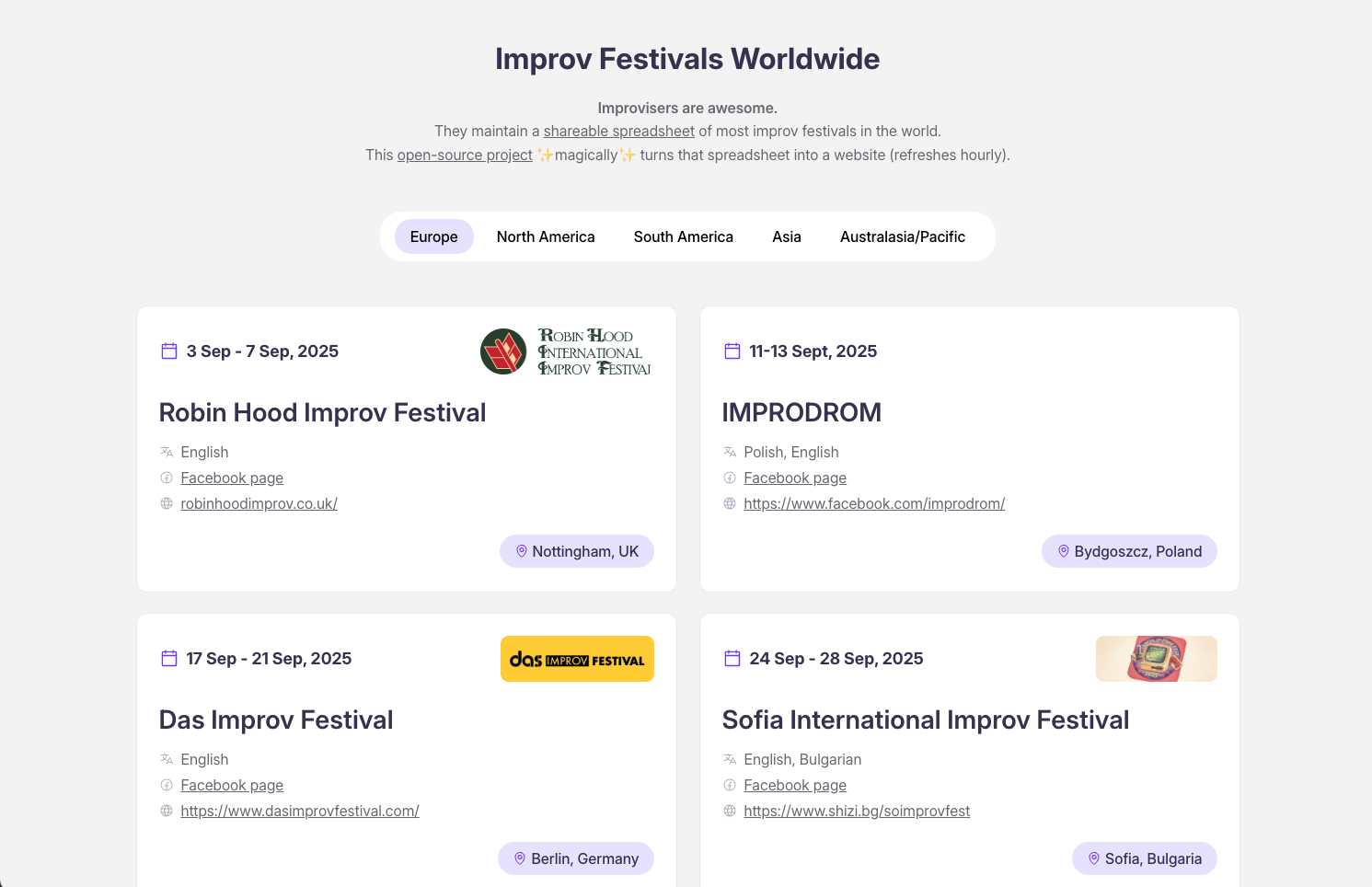

For two of those years, I was also a proud member of QUAKE, an Athens-based improv collective that organized jams, workshops, and collaboration sessions. Back then, beginners and experienced improvisers alike would often ask us where to find information about upcoming festivals, because they had no idea the Improv Festivals Worldwide spreadsheet even existed.

So what is this spreadsheet? It’s a publicly shared Google Sheet that lists most of the improv festivals worldwide. It’s kept up to date, openly shared and edited by members of the global improv community. I don’t know its full history or who first started it, so if you do, please get in touch so I can update my text and give proper credit!

I’ve wanted to turn that spreadsheet into a website for years. I started working on it about a year ago and only recently found the time to finish it.

The beauty of this project is that the community already maintains the spreadsheet, so there’s no extra burden of keeping data current. All I had to do was fetch it, format it, and display it in a more accessible way.

I didn’t implement every possible parsing check or data optimization, simply for lack of time. My goal was the cleanest, most straightforward solution, and I think the result turned out pretty decent.

For the UX, I experimented with different placements of the information, trying to figure out the best way for users to quickly find and focus on the most important bits—like the date, festival title, and location.

If you want to see all the different iterations in detail, check the image here.

Regarding colors, there wasn’t much of a deep reasoning process—mostly trial and error. I ended up between purple and orange, and purple won. Since I liked all of the options, I included CSS classes (.orange, .yellow, .blue, .green) that can be added to the body element to switch the color scheme.

This project is open source, of course, because I see it as a community effort.

So anyone can fork it, customize it, and host it. No attribution required.

Currently, the site is hosted as a demo on a subdomain here:

improv-festivals.radical-elements.com

You can check the GitHub page of the project, with its technical info too.

There's not a lot of documentation, as I feel the codebase is very minimal and pretty much self-explanatory (for people familiar with Laravel or MVC frameworks).

But feel free to contact me ([email protected]) for any info on the project!

My goal is to also create a dockerized version of it so that people can host it anywhere, regardless of their tech stack.

My hope is that another (or many!) developer(s) from the improv community will pick it up, host it under a proper domain (improv-festivals.com is available at the time of writing), and keep it alive.

This is a small token of gratitude to the improv community, which has shaped my life in many, many ways.

Thank you :)

]]>The pull toward adding more features to cover every possible need is always strong. It feels safer to expand than to refine. Yet the users who seem happiest are those who find coherence and clarity, not abundance. A clean, intentional UI may drive away some who want infinite options, but the ones who stay will truly feel at home.

So, instead of adding more features, we focused our remaining time on refining what was already there. Improving keyboard shortcuts, cleaning up dropdowns, tidying the codebase, making the product a happier place for both users and us as creators.

This is the slower path. The less flashy one. But it’s the one that deepens the product, rather than bloats it.

In tech, slower paths are often deemed as unproductive and scaling is treated like the highest good. Companies obsess over more. More features, more users, more growth. In general, capitalism rewards expansion. And don't get me wrong, I'm not saying that's always a bad thing. Maybe we wouldn't have advanced surgery techniques and mechanical wonders were it not for this call for constant growth. But in tech, this growth often comes at the expense of coherence and user happiness.

Personally, I think I’d rather have three Numenon users who are passionate about using the product, than twenty lukewarm ones who only tolerate it.

Depth asks for intentional limitation.

Take relationships, for example. I enjoy a wide circle of friends and acquaintances, and I’m happy to see them once in a while. But I can’t keep close contact with more than 5–6 people for long. Whenever I try, the quality of attention I give to those already close drops.

Meaningful relationships need presence and mental space. You have to remember what matters to someone, hold it with care, and be ready to ask, help, listen.

Sometimes that means making hard choices. When your capacity is full, it’s okay to postpone connecting with outer-circle friends so you can stay fully present for your inner circle. This isn’t about refusing new connections (people move in and out of circles all the time anyway), it’s about respecting the limits of attention and care.

I notice the same in hobbies and personal growth. If you want to deepen your relationship with something, you have to commit. I’ve done ceramics once a week, aerial acrobatics twice a week. All of those were very rewarding, but up to a point.

Practicing something daily has a fundamentally different effect than practicing weekly. It means restricting other hobbies, having less variety, but, perhaps, a lot more meaning.

An excerpt from another piece I wrote ( Every day ) about the value stemming from the ritual of daily practice:

A ritual isn’t just repetition. It’s an act of meaning, something you return to not because you must, but because choosing it again and again gives it weight. It becomes an expression of self-love.

I feel the need to clarify here that I'm not saying depth is inherently “better” than breadth. Sometimes you crave variety, exploration, the pleasure of trying many things. I’ve always called myself a "jack of all trades, master of none", and I usually meant it as a flaw. But, I’ve come to appreciate that this breadth brings richness, perspective, and flexibility that dedication alone cannot. I'm proud of the multitude it has given my personality and skills. Yet the sense of meaning that comes from devoted practice is something else entirely.

Both approaches can have value at different points in life. But in software, depth usually wins.

Depth requires choice. It requires letting some things go. Not because they don’t matter, but because your time, energy, and care are limited resources.

With software, this choice shows up in design. By being deliberate about which features exist and where they live, you may lose some users who wanted one extra button or two. But the users who stay will be happier. They’ll feel the clarity, the focus, the lack of clutter. In a sense, you’re training your own users. Not by restricting them, but by giving them a space that feels coherent and intentional.

The same goes for people, or crafts, or self-care. To deepen is to honor what you touch. It won’t scale in the way capitalism teaches us to admire, but it will create trust, meaning, and skill that breadth alone can’t offer.

Featured image attribution: “Wave, Night” by Georgia O’Keeffe — Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. ]]>

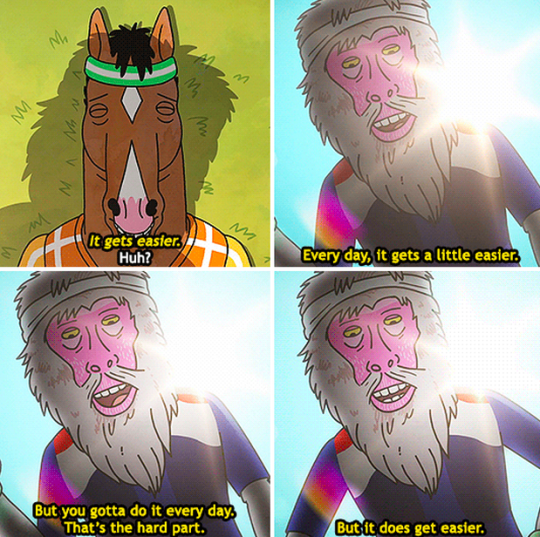

“It gets easier. Every day, it gets a little easier. But you gotta do it every day. That’s the hard part. But it does get easier.”

I think that line stuck with me because it reframes consistency. Instead of sounding like discipline which carries something forced (even punishment), it speaks to ritual and to devotion.

A ritual isn’t just repetition. It’s an act of meaning, something you return to not because you must, but because choosing it again and again gives it weight. It becomes both an expression of self-love and a way of belonging to something greater than yourself.

Doing something every day is less about grinding forward and more about sitting with yourself through a process, even when it feels stagnant, even when you can’t see the progress yet. That’s where the devotion lies, trusting that change is happening beneath the surface.

Growth is often invisible until suddenly it isn’t.

I think it resonated because it aligns with how I view growth. Not as a race or an accumulation of achievements, but as a slow, steady offering to yourself. Like watering a plant. Like writing a paragraph a day. It’s small, ordinary, almost imperceptible. A quiet act of showing up. And over time, that quiet presence becomes transformation.

]]>Back then, while building our first website, we did what every developer does. We filled the work-in-progress with nonsense, and the best example was the "Who we are" page. Instead of our portraits, we used troll photos as placeholders.

But they couldn’t be just any trolls. They had to match our characters, look good, they had to be art. That’s how we stumbled onto Olivier Silven’s sketches on Behance. They were so beautifully ugly. Perfect.

I even cropped them into avatars and even played with our logo so the trolls looked like they were breaking out of prison bars.

When launch time came, we were supposed to replace them with our actual photos. But we couldn’t do it. We’d grown attached. So we adopted the trolls, contacted Olivier, and he generously let us keep them, as long as we accredited him.

The trolls stayed with us. They even became part of our 404 page.

Over the years, they were always an icebreaker. New clients would check out the website before meeting us and would mention them right away. Some said the trolls convinced them they wanted to work with us. Others just laughed. Either way, it worked.

Fast forward to now. After years of working on big, closed projects, it was finally time to re-enter the market. The old site had served us well, but it felt ancient. We needed something new.

We struggled with a logo for months. Nothing fit. Then Alexandros said it: what’s the one thing people always associate with Radical Elements? The trolls. That was it. Finally something clicked. And who better to design our new logo than Olivier himself?

We reached out again, ten years later. He said yes. He worked lightning fast, turned our vague ideas into exactly what we wanted, and we made only the tiniest tweaks. The new Radical Elements logo was born, true to our history, consistent with our aesthetics, carrying our ridiculous little legacy into the future.

Olivier was fantastic to work with. Quick, responsive, and somehow inside our heads. You can see more of his work on his Behance and Tumblr pages.

--

PS: A few days ago, I was deep in bug-solving mode at my home office, frustrated. My partner came in and decided to mess with me by licking my cheek, which always infuriates me. I started banging my fists on the desk, exactly like our troll in the logo. He pointed at me, thrilled and laughing, and yelled: “That’s where it comes from! You are your logo!”

Apparently we’ve taken brand identity a bit too literally.

]]>One side effect that I recognize is that human ownership doesn't scale as fast as production does. This means that it will be easy for someone to create many systems via prompts, but will they vouch for them? Will it be viable to maintain or even understand the outcome?

Let's take a small web development agency, for example. I will say words and you will be able to fill in the gaps with your mind: Sales, proposals, WordPress, WooCommerce, templates, hosting, support. You have a picture. The average web agency uses all these tools and processes to scale, to sell more and code less. Quality should be acceptable, but no rocket science is involved.

Now this agency has the full AI deal: autonomous agents and whatever. Proposals will write themselves. The customer will be able to form the whole spec while talking to an agent via prompts. The website will be 80% ready by the AI. The humans now only have to curate the final content and possibly add some human flavor to the aesthetics.

Where is the web agency now? Why does it exist? What does it really do? One word comes to my mind: Insurance. And another word: Context. You want to delegate to a specialized company to take care of your "Context" to have a pool of all your prompts, assets, data, and history. To maintain this context over the years and ensure that it will be usable and reusable across your systems. Say welcome to the "Context Agencies".

What do we really control when it comes to AI? The input. And what else do we control that will shape the output? The Context. The Context is the function.

Output = Context(Prompt)

How do we improve the output? By ensuring that the Context is as optimized as possible for the task. Everybody believes that the job of the future is prompt engineering. Well, that is definitely not the case. Prompt engineering is not engineering. It's hardly a skill.

Context engineering is what can indeed become engineering and will have a great impact. More and more systems will not just ask you for a prompt, but will also ask you for context.

I can imagine companies in the future struggling with the decision to keep context management in-house or outsourced. And how are we going to handle sensitive data? Context permissions and security layers? Are the new APIs going to focus on how to return a thin, spot-on context instead of a JSON response? Are we going to build protocols to communicate this information?

Currently, the idea of context management is already in place. I could say that Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) is exactly that. But currently, you can't have access to that technique as an individual. At least not in a cohesive standard way. Another example:

Let's say we gather the marketing and the creative teams and brainstorm a new brand identity. We produce a ton of data in the form of ideas, sketches, conversations, mind maps, jokes, etc. Not all of this data will be useful, but some of it will be. Imagine that we could feed all this data somewhere. Then we classify it and curate it. The process doesn't matter. What matters is that now, this information is part of the history of our company. We accepted it as important enough to be retrievable in the form of a context, somewhere, somehow.

Now let's say that two years from this brainstorming, it's time to launch a campaign or something. The current team can access the previous brainstorming. Not as data. Not by browsing the mind maps manually or looking at discussions. But, when a member of the current team is going to ask the AI to do a task, she will feed the previous context and the AI will be on the same page. Better yet, it will have a sense of the company's history relative to the task at hand.

The example I gave has the following problems right now. How do we decide which data are going to be valuable in the future? How are we going to classify them, security-wise and content-wise? And how are we going to know how to use them? How to retrieve the correct context? I don't really have concrete answers to these questions, but I can imagine that the solutions to problems of that nature will shape a big part of future services.

]]>- Fail fast, fail often

- Fail forward

- Move fast and break things

- Pivot or die

And the list goes on

I don't know about you, but I'd be okay if I never read a similar phrase again in my life. It's not that they're wrong. They try to compress many truths into 3 to 5 words. But the compression isn't lossless, and the message can't be applied everywhere. It's not enough to just follow these concepts blindly. You have to understand why they exist. Otherwise, you'll most probably create a culture of chaos in your company and in your mind.

In order to begin an entrepreneurial journey, you have to have a vision and you have to be optimistic about the future. That's why everyone preaches to "fail fast", because knowing if your vision is a delusion as early as possible is critical. You want the minimum possible investment of time and money to get that answer. But not less.

Do you see the contradiction here? You have to exist in a conflicting state. Be optimistic about the future, but not that optimistic because you'll probably fail. So don't over-invest. But still stay optimistic that eventually you'll succeed, so don't let failure crush you. This isn't a simple way to live your life. This is a sophisticated state of existence. It's not easy.

Your vision is somehow a prediction. You predict that the thing you're making will appeal to a certain number and type of customers, at a specific point in time. This looks like a long shot regardless of the content of your vision.

The internal conflicts are all over the place. You have to have passion and believe in your vision, otherwise, why bother? But at the same time, you have to be open to the fact that you could be delusional or simply wrong.

The optimistic dreamer and the cautious realist

The optimistic dreamer and the cautious realist should live together and be productive. Good luck. Even if you know that this is the way to go, it's not a comfortable position, constantly trying to balance.

Starting something new means that you're passionate about your vision. But at the same time, they tell you that you have to be ready to pivot. And pivot, sometimes, means that maybe you have to compromise or adapt to something that you're not that passionate about. But hey, you did this to win, right?

One of the reasons I chose to be an entrepreneur is the freedom. The freedom to envision and build things. I'm sure that other people will have a different set of priorities. And that's the wonderful thing about entrepreneurship. You get to pave your own path. You get to travel your own journey.

All these clichés certainly compress a lot of wisdom, and although I have an aversion to buzzwords, I always try to unpack them and find the essence of them. There's so much knowledge out there, and I want to be open, to learn and enrich myself and my philosophy. But at the same time, I refuse to follow "orders".

I'm not here to solve a puzzle, I'm here to make an original painting.

]]>Sometimes they do. But often, they don’t.

More often, they know what they think they need, limited by a mindset shaped by the way they've always done things. They believe they know the solution to their problem, but they might not even have identified the real problem. Or they might only grasp 10% of the possible solutions. Or both.

And that’s exactly why they’ve come to you: because you’re the expert. You know things they don’t. But sometimes, let’s be honest, you don’t know either.

And that’s okay.

The myth of knowing

If I ever have children, I’ve promised myself one thing: I won’t pretend to have all the answers. When they ask me something I don’t know, I won’t mask my ignorance or give them a generic, half-assed explanation.

Instead, I’ll say: “I don’t know. Let’s find out together.”

Because in that moment, I’m not just offering honesty. I’m modeling something deeper: That the refusal to disguise not-knowing is a quiet form of courage.

And this response, in my opinion, teaches two crucial principles:

1. Ignorance isn’t a deficit. It’s a doorway.

We live in a world obsessed with certainty. But certainty can be a trap. When we tether our sense of self and our identity to always having an answer to everything, we start to fear the learning process, because it reveals the depth of our ignorance. We become defensive when faced with our knowledge gaps. Rigid. Vulnerable to confirmation bias. More on that idea here: The hedonism of certainty.

It's important to have a clear sense of our ignorance.

It keeps us humble, it keeps us alert. It stops us from becoming know-it-alls in a world constantly bombarding us with half-truths and misinformation. It prevents us from mistaking surface-level knowledge for real understanding.

Uncertainty, when embraced consciously, makes us better thinkers. More curious. More open. More rigorous. It keeps us honest in the current reality of echo chambers (algorithmic or otherwise).

2. Research is a skill, and a shared journey.

You don’t need a PhD to begin investigating something. In 2025, access to information is easy. But the ability to evaluate and synthesize that information? That’s a practice worth cultivating. And searching for answers can be a shared act, not a solitary burden.

(Honestly, How to use a search engine to find credible sources should be part of school curriculums.)

Now, how does this apply to client work?

Sometimes clients are explorers too

Clients may come to you with strong opinions or assumptions. But under the surface, they’re often unsure.

Maybe they know their market, but not how to position themselves in it.

Maybe they don’t fully grasp what they want their business to become.

Maybe they’re unsure how the web will affect them, because they’ve never done this before. There may be no data yet, just hunches.

As professionals, we often believe we’ve collected all the data after an initial round of questions. But I’ve found that if you keep asking, digging, gently pushing, there’s always more. And some of it might change the whole direction of the project (I’ve written about that here).

But what if you’ve asked everything you could think of, and you're still unsure?

What if your client simply does not have the answers?

Make space for shared uncertainty

You make space for shared uncertainty, that's what you do.

You turn that murky space from something awkward and uneasy into something that allows inquisitiveness and creativity. You help your colleagues feel comfortable and inspired in there too.

And then, your clients. They've declared their ignorance, you declare yours, and, together, you start searching for the answers.

This shifts the relationship from expert vs. client to co-explorers of an uncharted territory.

You research, map possibilities, test ideas, ask new kinds of questions. You present your findings, not as declarations, but as hypotheses. Then you discuss. And discuss some more.

You co-discover.

And yes, you charge for all of it. Please.

Because research is not free. It is skilled labor, and it is foundational to everything that comes next.

“By embracing uncertainty, you’re developing a culture that supports innovation and learning through experimentation... one that acknowledges testing new ideas will inevitably lead to some failures.” — William Jung, PO at Macquarie Group | Full article

Embrace uncertainty, let it be a tool.

Your job isn’t always to know. Your job could sometimes be how to not know well.

Clients don’t need you to have all the answers.

They need you to help them ask better questions.

To help them navigate uncertainty.

To stand next to them and say:

“We’re going to figure this out. Together.”

It’s about a Harvard case study, Carter Racing, as it was covered in David Epstein’s book Range. Students are presented with data on a fictional scenario and asked to make a decision based on it. Specifically, whether the company should race or not in the upcoming event.

The article (and the section of the book) describes the process through which the students made their final decision, using the data given to them.

Spoiler alert: Before you go any further, I’m about to spoil the whole point of the article. I suggest reading it first. It’s interesting, it’s short, and it’ll make the following make more sense.

The point of the article is that students spent all their time assessing the data given to them, which was incomplete, without stopping to think that perhaps they could request the missing data from their professor. The professor had mentioned multiple times, “If you want additional information, let me know,” but somehow, no one thought to actually do it.

What’s tragic about this is that the Carter Racing case study is a disguised retelling of a real-world scenario. The 1986 Challenger space shuttle disaster, where overlooking the missing data led to the death of all seven crew members on the mission.

There are many conclusions to draw from this story, but it felt strangely familiar, even though I’ve never been anywhere near HBS. And then I started to realize. We’ve been those students. We’ve been those engineers. Thankfully, we haven’t been in the position to be responsible for anyone’s life, but we have been responsible for our clients' budgets, our clients' clients' payments, and so on.

Solving the wrong puzzle

So often, a client comes to us with an idea, a need, or a problem. And so often we take that at face value, accepting that yes, this truly is their problem.

Of course we ask questions, many of them. However, the answers you receive can be outright misleading if the premise behind your questions is flawed.

This is the trap. Clients often come to us mid-thought.

They've already framed the problem in a specific way. They’ve already eliminated options, narrowed the scope, maybe even come up with a solution. Not because they’re careless or lacking insight. They’re just immersed in their own context. What feels obvious or irrelevant to them might be critical for us to understand the full picture.

They might leave out key constraints because to them, those are just obvious, everyday facts. They might not mention internal politics, budget or time flexibility, the bigger picture, or what they’ve tried and failed at before. That last one is the more frequent scenario and usually the most valuable part of the data. Most of the time, it’s not out of secrecy but because they assume it’s not relevant information.

And so, without realizing it, they give us an incomplete puzzle and ask us to find the missing piece, when the edges are all wrong.

The case for un-framing

This is why just asking questions isn’t enough.

One key part of the process, before we start asking or building, is to un-frame.

We need to rewind. To undo the thread and go back to the root, even if that means setting aside our clients' stated goals or proposed solutions for a moment.

Because if we start from a flawed premise, every answer we come up with, even the most brilliant one, will be answering the wrong question.

And if you think about it, that was the problem with Carter Racing too. The students knew they could ask for more data. But for some reason, no one thought to do it. The engineers too.

I think the reason they didn’t ask is the same reason we often don’t: we’re all stuck in our own mindsets. By nature, we’re limited by our own framing and interpretation. That’s why it’s useful to bounce ideas off others. Another mind will almost always offer a different angle, a new frame. Yet, instead of becoming this "bouncing wall" for our clients, we so often tend to accept the stated problem and rush toward a solution.

And it’s no mystery why. That’s what the human brain does best: seeking solutions. It’s an evolutionary trait that helped us survive and be here now. Our brains do not want to spend endless amounts of time digging for the true problem. That would be terribly inefficient in most cases. We love finding solutions. We don’t love relentless digging.

But as professionals, when we feel the urge to put our solution caps on, I believe that’s exactly when we need to stop and think: “Am I solving the right puzzle? Am I asking the right questions?”

]]>But still, writing code is an act of communication as much as writing is. Many fellow coders don't treat it like that, but they should. Coders compose worlds. Coding is about communicating with other coders or your future self. The way you express your program is a combination of experience, ideas, and opinions on how to structure processes and flows. There are countless opportunities and decisions on how you would express and solve the task at hand. Coders can and should be considered writers.

That's why I expect myself to be able to communicate my thoughts clearly in prose. If I can't do it in plain English, how can I expect myself to do it in code? In a way, these two go hand in hand. If writing is walking in the park, coding is riding a broken bicycle while drunk. So what am I? I am in the business of communicating ideas, constructing worlds, understanding workflows, and ultimately understanding my potential users, other people. Because not only am I a coder, I also sell a product. Other humans will use it. Both development and promotion are a unified process of throwing what once was in my head back into the world.

As a coder, I consider writing and promoting my product a chore. Something that doesn't suit my personality and the way my brain works. But as I dive deeper into it, I realize that maybe I am wrong. Maybe writing and expressing myself in English is exactly what I need. Deconstructing my vision and trying to get it across is like doing psychotherapy in public. I will certainly not be going to share my darkest thoughts, but I am going to be part of this evolutionary exchange of ideas and feelings.

So yeah, I am a full-time writer. I just don't accept it yet.

]]>I wanted to use Numenon and have someone else build it. I knew very well that I have a need that isn't covered by the tools available in the market, and together with Elvira we decided about half a year ago to take the leap.

I don't know if it will succeed as a startup - time will tell. But it's the first time in my life I feel such great satisfaction from the result. We built something we need and we use it every day, having replaced many other tools.

Something else that has great value is that Numenon potentially appeals to everyone. I can tell friends to go and "play" with it. Organize your personal life. Use it in your company or department. Use it for research or your next music album. It's really that versatile.

Numenon right now is a SAAS knowledge management system. Parts of it might remind you of Notion or Obsidian or something similar. We give you the freedom in how to structure information and make connections by creating a graph. You can use this graph in any way you can imagine. From building a CRM to creating a board game (we have beta testers doing this).

The concern for Numenon was that it should stand strong both theoretically and practically. We achieved this and it's already a very useful tool for quite a few people.

Now the vision is to develop it in the following areas: Collaboration, Security, Interactivity and AI.

]]>It happened to be an opinion I already agreed with. So, when the video ended, I noticed in myself a sense of satisfaction, a quiet pleasure. And I thought, "A-ha! Gotcha!" I had caught myself in a moment of joy, purely stemming from confirmation bias. A simple process of my stupid little brain going:

"I believe x about the world. I am now presented with data supporting x. Oh yes, so nice. I was right. I am safe. I have understood the world. I know how its cogs turn. I am safe."

I like to think of myself as a critical thinker. A skeptic. An inquiring mind. I take pride in the idea that I hold my beliefs lightly. That I don’t associate my personal value with my beliefs and can therefore shift my opinions when presented with new data.

But it seems I, too, am a human being, drenched in insecurity, burdened with the fear of this chaotic, unpredictable, uncontrollable world. And I, too, have moments where I take pleasure in a false sense of certainty and in the idea of control, of clarity, of having peered through the glass to see the hidden levers at work.

And it was in that exact moment, where I felt that pleasure, that I understood. It’s precisely when I detect that feeling that I need to be as vigilant as ever. That’s where we fall victim to our own biases and insecurities. That’s the moment to challenge our beliefs, to feel exposed, to embrace the fear of uncertainty.

It's not a coincidence that all conspiracy theories, half-truths, and pseudo-intellectual mambo jumbo play precisely on that human need for certainty. They present themselves not as possibilities or perspectives, but as absolute truths. They package themselves as airtight narratives, neatly tied together with pseudo-evidence and emotional appeal. They offer certainty beyond doubt, a place where everything makes sense, where no gaps remain, and no questions linger. They give you both the questions and the answers, pre-framed within their worldview. And by doing that, they don’t just feed you information, they erode your curiosity. They disarm your capacity to ask new or different questions, to explore beyond the frame they've set. It's not just misleading, it’s paralyzing.

After watching the reel, I looked up the papers mentioned and read more about the topic. As it often happens with complex matters, things weren’t as simple as the person in the reel made them seem. I had to shift my point of view. I had to accept that it’s one of those cases where nuance matters. And that, based on the data I could find, I couldn’t comfortably land on either side. I had to sit in that very uncomfortable middle ground.

It’s an awkward place. I imagine it as a chair that looks normal but whose seat is ever so slightly rotated, just enough to make sitting on it feel wrong. Or a ledge with a few sharp spikes that never quite let you settle. Not painful. Just uneasy.

But the more often you choose to sit there, the more you recognize that so much of life exists in that in-between space.

And still, it doesn’t get easier. You thought I’d say it becomes second nature, but no.

It remains unsettling, if not terrifying, at times.

But you do learn to live with it.

And more importantly, you learn to look for security elsewhere: in a flexible belief system, a resilient mind, a healthy lifestyle, in deep and meaningful relationships.

But opinions?

Those mofos won’t make you feel safe.

You better let that idea go.